Tuesday

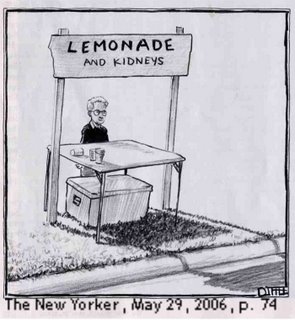

Last Sunday: I was talking to a fellow social worker about the move to set legal procedures for kidney trades. He mentioned that, as a social worker involved with preparing people for transplants, he is for that change because, when it is made, it will actually offer more opportunities for everyone waiting for kidneys. Right now there are many people who are

waiting for a cadaver kidney who could find a trade. After the trade policy is written into law, it will increase the amount of trades, which will have a ripple effect on the number of people who can get cadaver transplants because it will clear out many people on the waiting lists.

This is a good segue into my thoughts on the ethics of live transplant. There are ethical arguments and conversations going on about virtually every area related to transplants, including: ’live transplants’, ‘cadaver transplants’, ‘advertising for organs’, ‘control over transplants’, ‘free choice and organ donation’, ‘paying for organs’, ‘religious questions’, and ‘living donors’. Writers addressing transplant ethics tell stories to illustrate their perspectives, such as a story told by Arthur Caplan* in Science & Theology News Online.

(Todd Krampitz) “…got a directed donation last year from a cadaver source. … He was the fellow who put up billboards around the Houston, Texas, area asking people to donate specifically to him if they died or if they had a loved one who died. Todd Krampitz was a young man, he was only 33 years old, when he found out his liver was failing due to cancer. He mounted a campaign with his funds and money that he raised, and put billboards up to beg for a donor. And he did get a transplant in late August of last year. He just died only nine months after his transplant.

"The problem with his case was that, from the point of view of the transplant community, he was not a strong candidate to get an organ. They didn’t think he would survive a transplant given the nature of his cancer, which was aggressive and very likely to take his life. It is unclear, in fact, that he lived any longer post his transplant than he would have if he had not gotten a directed cadaver donation and a transplant.”

Caplan’s point, and argument is that the “transplant community” should be able to direct who gets transplants and who doesn’t get transplants. Someone needs to determine who is most appropriate for a transplant and all the details surrounding the transplant (when, cost/benefit, and resource allocation). Caplan argues that these questions should not be made by individuals (people advertising for an organ and those donating an organ to an individual) because we citizens are all paying the bill since we pay taxes that support training doctors, contributing to Medicare and Medicaid. In his mind, “Directed donation unbridled and unregulated, either living or cadaver, can, as the Krampitz case shows, undercut the efficacy that ought to be obtained from the yield of scarce organs.” This is a valid argument from the utilitarian point of view: ‘the greatest good for the greatest number’.

However, when a person is in the situation of needing an organ and they have resources in a “free” society, they will usually use their resources (do what they can) to get what they want. This needing-an-organ-situation is a serious thing to those of us who need one! Depending on how critical and immediate the need is for a life-saving organ transplant, I suspect people with resources intensify and accelerate their efforts at getting what they need to continue living. Are there any among us who like the idea of sitting idly by while our life peters out waiting f

or an organization (or a bureaucracy) to find an organ for us?

or an organization (or a bureaucracy) to find an organ for us?We all know that a rich person needing an organ will get one because they have the financial resources to purchase an organ in South America or Southeast Asia or in any third world country. One view is that the third world exists to supply the dominant societies. (I’m looking for a comment from Hans here!) And even in the dominant society, the wealthy don’t usually play by the rules of the common folk, so even though we may eventually legislate ‘appropriate’ methods for organ transplant, there is a segment of our society who will not have to play by those rules.

So, I wonder, what is the difference between someone who uses financial resources to purchase an organ, and someone who uses their creative resources to publicize and promote their organ needs? Mr. Krampitz utilized some financial resources and a lot of creative resources to successfully ‘sell’ the idea of giving him an organ. Would it have been more appropriate if he had convinced the public that giving him an organ would benefit the whole of Houston? Perhaps it is more ethical for prospective organ recipients to have to show how many good deeds they will do with their new organ?

I venture that, along with some organization deciding who is worthy of an organ, based on the cost/benefit, immediate individual need, and responsible resource allocation, perhaps there should also be an evaluation of the recipient’s potential constructive benefit to society. Then the determining questions might include, “Will the person use their new organ responsibly?”; “Is a social worker worth more to society than a salesperson?”; “Will the recipient vote to support the ruling party?”; and “Does the recipient have the correct moral fiber?” Don’t we want to find out if organ recipients will be good-deed-doers? I would be more in favor of giving an organ to a good-deed-doer than a professional athlete. But, do I represent the values of the organization that will be responsible for determining who gets what organ and when?

These are all mighty questions. I carry them to what some people might consider to be the absurd conclusion to point out that ethical discourse can be simply an exercise in looking to extremes in many cases. All the real ethical questions and considerations have been elucidated and argued for generations. Now, we are left with telling stories and using them to support our own beliefs. In a post-modern world all stories are valid and we are left to our own devices in figuring out which stories (narratives) we want to stand for. And, of course, any discourse is incomparable when discussed from an academic versus a personal perspective.

I guess I believe that ethics comes down to a personal set of values that each person must tap in any given situation (Fletcher’s Situation Ethics), and that it is very difficult to legislate values without allowing the SPGs, PACs, lobbying groups, and advocacy groups to control the process. Therfore, we, as potential recipients of organs, need to review our options and hopefully find a special interest group that we can agree with, and then join that group to ensure that it reflects our beliefs and values. In the area of transplants, I like the UNOS group because they are interested in one legislative agenda that I agree with: making it possible for people on the list for transplants to trade their live donors who don’t match with others who do match.

We also need to do what we can to educate our friends and neighbors about our particular world (in my case, Kidney Dialysis &Transplant City) and hope there is someone out there who wants to partner with us in our transplant adventure. That’s the way I see it.

* Caplan, A. (2005) The ethics of living organ donation. Retrieved June 19, 2006 online from the Science & Theology News (Online Edition), available at: http://www.stnews.org/rlr-1279.htm

El Milagro: Gladys cannulated me and did a fair job. Phyllis reported that she and Diane got suspended for a day for the mistake with my dialyzer and added, "as well we should have.". I was curious about why today (a holiday) wasn¹t like a Saturday, when I can slip in early, and she replied that the early business is basically over, since, as of this week, every chair in

every shift is full. There are five new people coming onto my shift this Thursday, transferred from another center that is being redecorated (or, renewed or something).

Today I am watching the amazing match between Germany and Italy... where it goes into the second 15 minute overtime period and looks like it¹ll end up with free kicks, which Germany always wins and Italy usually looses. Then, all of sudden Italy scores! And then, a minute and a half later, they score again... and it¹s over: Italy beat Germany (the favorite)!. WOW

Notes: In at 73.6 Kg, and out at 72.0 Kg.

1 comment:

Since Jack has called me out of my lurkdom I'll try and make some response to his post on the ethics of transplant aquisition. Jack notes that we are now living in a world in which the body of the subaltern classes becomes available for harvesting to serve the dominant capitalist class. This is to some degree shocking but at the same time it is simply an extension of the logic of capitalism as it applies to the body. After all for capitalism the body is the source of all profit. Whether it is being used as slave labor (waged or unwaged), addicted consumer, or organ crop-the logic is the same. The body is only useful to the degree it produces profit or benefit to the capitalist class. In this logic there is no sense of the body in its full capacity to produce a life or death on its own terms but only its utility to capital and the capitalist class. The fact the parts of the body can now be marketed as a new commodity with the full logic of exchange value just confirms that the moment of post modern capitalism is the moment of what Marx talked about as complete subsumption in which everything is for sale and operates within capitalist logic. In this we lose the possibility of the love and hope engendered by the concept of freely donating one's organs so another might live (an actual ethics of care.)

This moment of postmodern capital does, as Jack points out, evicerate the possibility of big T truths or stories that are true for everyone. However, there are two edges to postmodernity. The one capital builds its new logic on is the logic that leaves all stories equal and available for exchange as ideological structures for emerging discourses of the ruling class. The other side to this is the postmodernity of Derrida and Foucault who point out that deconstruction is the art of finding the hidden stories of resistance and struggle buried under the master narratives of the dominant class. In this all stories are not created equal. Stories are the battlefield of class struggle and insurrectionary possibility. As Deleuze and Guattari would have it-- within each narrative of order and control there is both a warning to flee control and domination as well as stories that allow for passage through and beyond the story of the current regime of power. Perhaps these passwords are the stories we need to create a new ethics of love and community that includes the body and its organs.

Hans

Post a Comment